The wonderful Function of Michael Deakin

Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 1 September 2014

Function was a mathematics magazine published by Monash University until 2004. It was expressly intended for high school students, with the purpose of presenting articles "for entertainment and instruction, about mathematics and its history". Function was very ambitious and it was very, very good.

Your Maths Masters have created a temporary (and clunky) online home for Function on our website, with the articles discussed below linked there. (We haven't tested all browsers, however Firefox appears to work.) Hopefully a more permanent home can be found in the near future.

Function first appeared in 1977, which happened to be the year a young Maths Master was undertaking HSC (the precursor to VCE). On the advice of his wise teacher (a hello wave to Mrs. Baker), your Maths Master shelled out 90 cents for the first issue of Function; he had never seen anything like it. Function was about mathematics: current research, historical roots, and playful problems and observations. That is not to deny the quality of HSC mathematics at the time, which was challenging and provided an excellent foundation for the university studies to follow. But Function was different. Every issue opened a new and unexpected window to the world of mathematics.

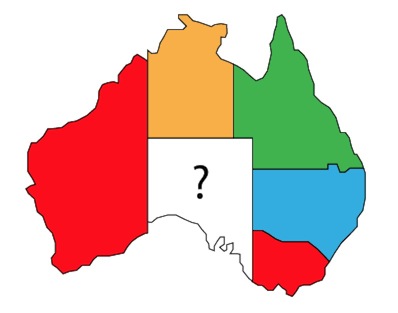

To give an example, Function's very first issue featured an article by one of our mathematical heroes, John Stillwell, on the four colour theorem. To understand what this famous theorem says, consider the following familiar map:

The problem is to colour the map so that no two states sharing a border are coloured the same. In our attempt above we've (somewhat carelessly) employed four colours to take care of all but one state, which would now require a fifth colour.

The four colour theorem states that we could have done better: the map above, and any map, can be coloured using just four colours. (In fact it is easy to see that three colours will suffice for our map above.) It is an enticing problem because it is so easy to understand and so, so difficult to prove. The theorem was only proved in 1976, and only with the aid of a computer to analyse over a thousand special cases. There still does not exist a computer-free proof.

Function provided an excellent article on what was then exciting and new research. It gave a clear description of the four colour problem together with an engaging historical overview. But even more engaging, the article included the essential details of the five colour theorem: for any map five colours will suffice. The argument wasn't easy going for a school student, however no mathematical background was required and with patience one could work through it. Stillwell's article was a beautiful illustration of how difficult a simply stated question could be, and how a little insightful mathematics could (at least in part) conquer that difficulty.

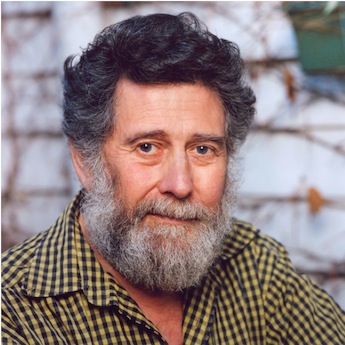

Function was continually offering such wonderful articles, and more than anyone the sustained quality of Function was due to Mike Deakin. He was an editor for Function's entire existence, chief editor for most of that time, and he was far and aways Function's most prolific contributor. Mike wrote 128 articles (as near as we could count them), cowrote five others and made Lord knows how many contributions as an anonymous editor. Many mathematicians, particularly Monash mathematicians, appreciated the value of Function and made very significant contributions. But Mike Deakin was Function's heart and soul.

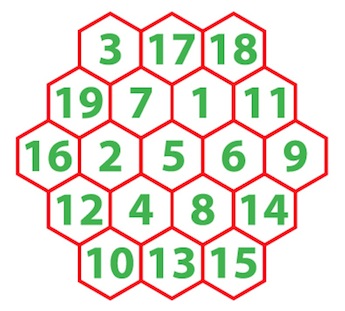

It is impossible to convey the breadth of ground covered by Mike's articles. His first contribution, in Function's second issue, was on catastrophe theory, important work on abrupt mathematical changes that became fashionable (and faddish) in the 70s; it was a perfect topic for Function, a new and alive research area that could be explained just using polynomials. Mike's second contribution, in the very next issue, was a lovely article on magic hexagons, which turn out to be an astonishing variant of the more familiar magic squares.

Above is an example of a magic hexagon, with the numbers 1 to 19 filling the cells, and with the numbers in each row (no matter the row's length or direction) summing to 38. The reader is invited to search for another magic hexagon (but may wish to consult Mike's article for a hint.)

Mike wrote often on the history of mathematics, including a fascinating article on Hypatia, generally considered to be the first woman mathematician. Mike carefully considered all the evidence to support such a claim and, somewhat disappointingly, concluded that Hypatia was probably not a mathematician of any stature, that she was likely "a transmitter of mathematics, not a creator of it". Hypatia was undoubtedly remarkable, "widely respected as a teacher - eminent, influential, even charismatic ... But we have no evidence that she was anything more than this."

Mike also wrote very thoughtful articles on mathematical culture. He investigated the pre-pre-history of mathematics, the ancient remnants of mathematical thought that are evidenced in language. Mike wrote critically, and unapologetically, on the differences in mathematical cultures, on the distinction between "high numeracy" and "low numeracy" cultures. (Such concerns later led Michael Deakin to write a careful and scathing critique on an aspect of the Australian Curriculum, on the inflated role assigned to (essentially non-existent) Aboriginal mathematics.)

Michael Deakin was a careful and critical scholar. However Mike was also light on his mathematical feet, and he made many whimsical contributions. One of Mike's earliest contributions to Function was a short and clever argument that 2 + 2 = 3 (for small values of 2). In a similar spirit, Mike offered a mathematical argument that most people who have ever been born on Earth are still alive: so, at any time in the future, the odds are we'll be alive! Many more of Mike's contributions were written in a similar spirit.

Writing about Michael Deakin and his incredible output of clear and engaging mathematics, one's thoughts invariably turn to the brilliant Martin Gardner. As a mathematical populariser no one can compare to Gardner, however Mike Deakin is as close as Australia has ever produced. And more than a populariser, Mike was an active mathematician and historian. His many interesting and original contributions appeared in American Mathematical Monthly and the Gazette of the Australian Mathematical Society, and in many other journals.

However it is Mike's inspiration to young mathematicians, and in particular his amazing work on Function that will be Mike Deakin's enduring legacy. In 2003, Mike received a prestigious and much-deserved award from the Australian Mathematics Trust, honouring his great work.

Our colleague and good friend Michael Deakin died earlier this month. He is missed, and he is irreplaceable.

Burkard Polster teaches mathematics at Monash and is the university's resident mathemagician, mathematical juggler, origami expert, bubble-master, shoelace charmer, and Count von Count impersonator.

Marty Ross is a mathematical nomad. His hobby is helping Barbie smash calculators and iPads with a hammer.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.