Pascal's shell game

by Burkard Polster and Marty Ross

The Age, 15 April 2013

Mathematics is everywhere! Your Maths Masters have been promoting this message in column after column, seeking to tease out the mathematics in the most unlikely scenarios. Nonetheless, on occasion even we are taken by surprise.

One of your Maths Masters visited a fishmonger’s recently, and he happened to espy the beautiful shell of a giant sea snail. There was definitely mathematics to explore in the shape of the shell, however that’s not what intrigued him.

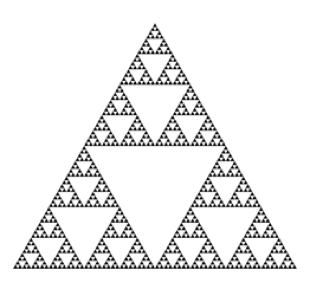

Take a careful look at the pattern that adorns the shell. It is strongly reminiscent of Sierpinski’s triangle, a beautiful and famous geometric construction:

Sierpinski’s triangle is described as being self-similar, since small portions of the triangle are scaled down replicas of the whole figure. It is also commonly referred to as a “fractal”. (However, for reasons we'll go into another time, we try to avoid using the “F” word.)

To construct Sierpinski’s triangle, you’ll need a piece of paper, some sharp scissors and an infinite amount of time. Begin with a solid equilateral triangle, as pictured on the left below. Divide that triangle into four smaller equilateral triangles and cut out the middle one. Next, repeat the procedure with the three remaining equilateral triangles, leaving nine even smaller triangles. Now repeat the procedure yet again, and on and on, forever. The specks of dust left at the very end comprise Sierpinski’s triangle.

But how does this stunning pattern wind up on the shell of a sea snail? Nobody knows.

One theory encapsulates the process we’ve just described. So, the shell begins with a solid triangle painted on it, and then the Shell God comes along, removing all the little triangles with a magic eraser. However, this is not a popular theory.

Whatever natural process creates the shell’s pattern, it seems very unlikely that it is directed by some such overarching design. The pattern is much more likely to be the consequence of simple biological rules acting at the cellular level.

It is not known how the shell might come to obey such rules, but we do have a guess at what the rules themselves might be. There is a cellular approach to creating Sierpinski-like figures that might (or might not) mimic the process occurring in shells.

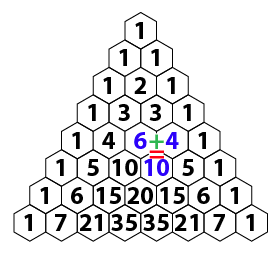

Let’s begin with an ultra-famous number pattern:

This is the tip of Pascal’s triangle, which is full of amazing mathematics. Most importantly, the rows consist of binomial coefficients.

There is also a very simple rule for growing Pascal's triangle row by row: the number in any cell is just the sum of the numbers in the two cells directly above it. For example, as highlighted in the diagram, the 10 in the sixth row is the sum of the 6 and the 4 above it.

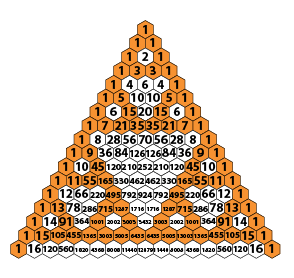

Now comes the Sierpinski part. Coloring in all the cells containing odd numbers, the top of Pascal’s triangle transforms into a finite version of our Sierpinski triangle:

This lovely and simple construction suggests a very natural model for the production of snail shell patterns. A snail shell grows in thin layers that are added onto its lip; in our mathematical model these layers are the horizontal rows of hexagons.

Then, the colour of the hexagons in each new layer is determined by the three simple rules for adding odd and even numbers:

o + o = e, o + e = o, e + e = e

This is all very neat, and it is based upon a type of biological mechanism that can be observed, where existing cells determine the characteristics of the new, adjacent cells. Indeed, there is an entire book devoted to examining shell patterns from this point of view. (There is also a lovely book devoted to picturing patterns in Pascal’s triangle similar to our even-odd colouring.)

However, we mathematicians should avoid being overly cocky about the explanatory power of mathematics. Just because our model “feels right”, and is probably the simplest model to replicate the characteristic snail shell pattern, that does not imply that our model captures the natural processes at work. Until biologists discover a natural even-odd mechanism in shell formation, our model remains nothing more than a guess.

Nonetheless, whether or not our model explains nature, it does illustrate an important and powerful principle: astonishingly complicated patterns can arise from the simplest of “local rules". That is, rules that only permit (mathematical) cells to affect immediately neighboring cells can result in striking global phenomena.

This is the theory of cellular automata, of which the most famous example is Princeton mathematician John Conway’s Game of Life. The implications of Conway’s “simple” game are quite astonishing. In particular, within the Game of Life there exist universal computers, which can (theoretically) perform any computation of the most powerful computers we might create. Nonetheless, Conway’s game is not much more complicated than our shell game: there are four rules instead of three, and the game is played on a square grid.

William Blake encouraged us to see a world in a grain of sand. We might not be able to accomplish that, but we can most definitely see some complex beauty in one stunning seashell.

Burkard Polster teaches mathematics at Monash and is the university's resident mathemagician, mathematical juggler, origami expert, bubble-master, shoelace charmer, and Count von Count impersonator.

Marty Ross is a mathematical nomad. His hobby is smashing calculators with a hammer.

Copyright 2004-∞ ![]() All rights reserved.

All rights reserved.